This piece describes a recent business model innovation that is paving the way to addressing not only unsustainable practices within the existing apparel industry, but also, its failings in adequately catering to developing and rural populations. The two UN Sustainability Goals which will be the centre focus are the following:

Goal 3 – Good Health and Well-Being

Goal 12 – Responsible Production and Consumption

The apparel industry has seen tremendous growth over the last decade. The McKinsey Global Fashion Index predicted industry sales growth would nearly triple between 2016 and 2018, from 1.5% to between 3.5-4.5%. This has provided numerous benefits, including vast employment opportunities across various parts of the world. However, the tremendous increase in global scale and the emergence of what is now known as “fast fashion” – some 60% more garments are purchased yet kept half as long vs. 15 years ago – have put the apparel industry on the center stage of the looming sustainability crisis.

As an example of one of the primary sustainability pitfalls; almost 20% of the world’s water waste is churned out by the fashion industry. It is not simply usage; synthetic chemicals used in refining textiles are released back into water reserves and thus have contributed meaningfully to global industrial water pollution1. Cotton, for example, is a notoriously water-intensive crop and one of the most widespread materials used in clothing and footwear. Through its heavy consumption of water, cotton cultivation has contributed to the depletion of natural sources of water in the vicinity of cotton farms. Water-usage aside, this in turn has had a scalable impact on the communities surrounding them, causing economic and health issues as dependent villages and individuals are left with sparse pools of contaminated water, previously much needed for crops, food and basic sanitation. The knock-on effect on development, health and well-being of these communities is as such compromised.

Other materials used in the apparel industry, some touted as “greener” options vis a vis cotton, have also laid waste as toxic chemicals and waste from processing fibres have also had detrimental effects – one such example is the processing of well-known viscose. Whilst the broader industry is slowly waking up to these threats and increasingly companies look to ensure sustainable production and consumption practices, the progress which has been made still remains a long way off from the targets of the Goal of Responsible Production and Consumption. Changes to the existing infrastructure, culture and reliance on existing time-tested materials from a garment quality and durability perspective will be difficult to implement to the extent that the apparel industry becomes fully sustainable. As with many other industries, there is still a long way to go before social and environmental prerogatives go hand in hand with financial incentives.

From the perspective of Goal 3, Good Health and Well-Being, the pitfalls of the apparel industry are rampant both on the production and consumption sides. As it relates to production, apparel companies are heavily reliant on supply chains located in developing economies, primarily due to their access to low cost raw materials and labour. As these value chains are buyer–driven, much of the bargaining power lies with large retailers and manufacturers who act as package suppliers for foreign companies to whom the goods are exported to, this in turn restricting growth potential of local suppliers and smaller businesses. Retaining supplier contracts with foreign apparel companies is typically a constantly competitive landscape, and as such the pressure to keep costs low hampers growth potential for these suppliers and unfortunately also incentivizes manufacturers, to some extent, to cut corners in terms of safety, abiding by regulation and ensuring fair labour conditions. Recent years have seen a number of supply chains in developing countries come under fire for instances of marked social issues including unfair migration practices and forms of modern slavery.

On the consumption side, many populations in developing markets rely on second-hand clothing and other charitable organisations for clothing and footwear. The lack of access to basic apparel can and has been a hindrance to many people in developing nations, restricting even basic activities – for example, children without adequate footwear can find it difficult to attempt the long treks needed to get to school. The knock-on effect can be tremendous as education and sanitary conditions are compromised. This is particularly significant with clothing and shoes for children, as they consistently need new items to keep up with growth. Without an efficient system for upcycling and sourcing new pieces for the younger portions of the population, having adequate basic apparel for children is a difficult challenge to overcome. Unlike Goal 12, the industry has already made a number of moves to combat this, with numerous charitable organizations redirecting un-used or second-hand apparel to those in need; that said, without a self-sustaining business model, the cycle continues and ultimately these populations become dependent on external help.

We also identified a few additional goals that are to a certain extent touched on by this business model innovation –

Goal 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation

Goal 8 – Decent Work and Economic Growth

Goal 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities

Goal 13 – Climate Action

As detailed above, the apparel industry has a widespread impact across many of these SDGs.

The Shoe That Grows—An Answer to Fast Fashion?

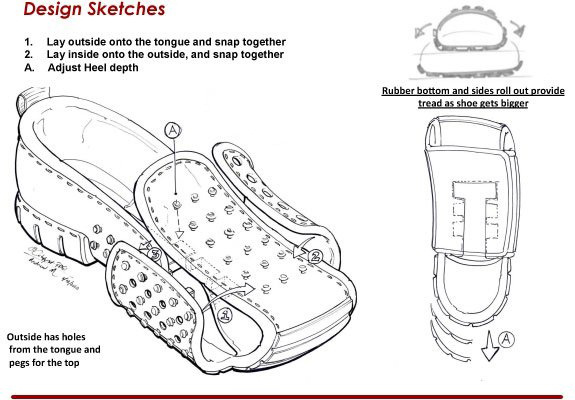

“Because International” is a company that produces The Shoe That Grows—children’s footwear that can increase by up to five sizes and is adjustable in three places (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Initial sketch design

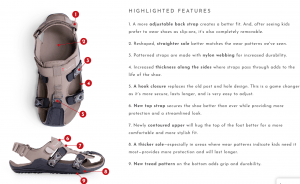

Figure 2: New design

https://becauseinternational.org/the-shoe-that-grows-new-design

This concept addresses the issue of buying and replacing shoes too often for fast-growing children, especially for low-income families. The shoe is offered both as a product for children living in poverty in developing countries and as a shoe for consumers in developed markets, with slight differentiation between the two products (Figures 3, and 4).

Figure 3 – The Shoe That Grows – Developed Market Product Line

Figure 4 – The Shoe That Grows –Developing Market Product Line

Social Benefits of the Shoe – SDG 3: Good Health and Wellbeing

The Shoe That Grows addresses health and wellbeing issues related to being shoeless in developing countries. For many children in these areas living in poverty, going shoeless or wearing shoes that are too small exposes them to soil-transmitted diseases and parasites. Children who get sick miss school, and exposure to parasites can reduce school performance and attention. In addition, not having access to shoes makes it difficult for some children to walk to school over long distances. With the Shoe That Grows, children have access to footwear that will last them through five different sizes, and the chance that they will have to go shoeless decreases.

Social Benefits of the Shoe – SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

The Shoe That Grows also contributes to the responsible consumption and production goals of SDG 12. Since these shoes are designed to last for five years through five sizes, consumers need not purchase and dispose of shoes as often when children grow. This contributes to less waste in the children’s shoe sector, and a shift away from fast fashion trends that emphasize buying cheap and short-lived products and replacing them often. Especially for consumers in developed markets, buying and using the Shoe That Grows could translate into saving four or five pairs of other shoes that would otherwise have been purchased to keep up with growth spurts.

Financial Benefits of the Business Model

Financially, the Shoe That Grows outperforms traditional children’s footwear both thanks to its product characteristics and its local supply chain. Since the product is marketed to last for five years, it commands a higher price than similar sandals both as a product for children in poverty and in its more developed markets (US$ 20, and $59 respectively). NGOs, development agencies, and parents alike can justify this higher price as the shoe is a long-term, rather than short-term investment in children.

In addition, the shoes are largely produced in the developing countries where they are used, meaning that Because International takes advantage both of lower wages in these countries and lower distribution costs to end consumers in developing countries. This focus on producing the shoes in-country also benefits the local economies of the end users, helping boost wages and create employment opportunities. These benefits fall under the SDG goal 8, Decent Work and Economic Growth, but there are also spillover effects into SDG 13 (Climate Action) through the reduced carbon footprint thanks to shorter shipping distances.

A Virtuous Feedback Loop in the Early Stages

Up to a point, the Shoe That Grows represents a virtuous feedback loop. Certainly, as sales of the shoe increase and adoption grows, the environmental and social benefits of the shoe will increase. Since a portion of the profits from the developed market product line are reinvested in the developing market product line, there is also a link between growth in sales and the impact of the Shoe That Grows in developing areas.

However, there is also a fundamental contradiction between the environmental benefits that the shoe creates through decreased waste and the decrease in demand for the very products it sells. If the Shoe That Grows were to become widely adopted, one could expect children’s shoe demand to actually decrease because children’s shoes would last so much longer that parents would need to buy fewer shoes. Therefore, if the the product were to scale and be successful at achieving the social and environmental goals it has set for itself, it would undermine its own success by decrease shoe demand.

Potential Costs and Risks of this Innovation/barriers to scaling–BOP customers

The key concern for the Shoe That Grows is whether it is serving an actual need for BOP customers. It is not currently clear the extent to which children going without shoes is driven by growing feet. Typically, a BOP family will have multiple children with a relatively short timeframe between children. As such, as one child grows out of a shoe, it can be handed down to younger siblings. In tight-knit communities, it may even be possible to share shoes between families and therefore a larger pool of children. The reasons for children not wearing shoes may be that shoes (irrespective of size) do not last long enough through the wear and tear of daily use and that shoes get too dirty not to be replaced.

As such, the durability of the Shoe is of utmost importance. BOP children will likely wear the same pair of shoes every day, and even though the Shoe can “grow” with feet size, if it does not last the heavy use, they will be routinely disposed of just like other pairs of shoes.

There are further issues around hygiene about wearing the same pair of shoes for five years. For BOP customers who may not have the means to routinely clean the Shoe, the Shoe may accumulate dirt and germs over the years, leading to infections and diseases.

Moreover, it might be important to BOP families to buy a new pair of shoes each year as a signal of status or as a form of aspirational consumption, rather than using the same pair for five years.

Finally, there might be other, more effective ways to address the problem of shoeless–ness in developing countries. In developed markets, even if families do not need shoes in a new size each year there is a culture of disposing of perfectly functional shoes among higher income consumers. If these were collected and distributed in appropriate sizes and markets, this could help to solve the shoeless-ness problem through a closed-loop system, without creating new products at all. However, it may be that even BOP families prefer to use shoes they have purchased new themselves (as opposed to second-hand or charity shoes). In addition, a shoe serving one child for five years as opposed to five different children over five years may reduce the risk of disease transfer.

Potential Costs and Risks of this Innovation/barriers to scaling—Developed country customers

As mentioned, many developed country families will buy and own multiple pairs of shoes at any one time. Consumption is typically driven by fashion trends and desire for new products, rather than needs. In developed markets shoes are not viewed as basic commodities, but rather fashion-statement items and a way to express individual identity. As such, wearing the same shoe for five years might not appeal to consumers, who want to stay on top of seasonal trends.

Steps to mitigate risks

One business model innovation that could help Because International address the issues of product durability would be to redefine itself as a footwear as a service business. In this way, the firm would sell not just a product, but a guarantee of footwear that fits a child’s feet for five years. Such a service-oriented model would include things like repair, cleaning, and fitting and refitting of the shoe.

In developing markets, this after-care service can help educate BOP customers on how to take care of the shoes, which can lengthen the lifespan of the shoes. Further, BOP customers, parents and children alike, can be educated on how to maintain a good level of cleanliness and hygiene of the shoes, thus improving the physical health and wellbeing outcomes of the children.

In developed markets with more affluent customers, such a value proposition might encourage parents not to needlessly purchase shoes. It could also improve the value proposition of the Shoe That Grows, meaning that it could command a higher price as a full shoe and shoe-care firm.

Potential negative externalities of the Shoe and how to address them

In developing markets, there is a risk that the Shoe could harm or displace local or artisan shoe manufacturers countries. If some families who previously purchased shoes from domestic shoemakers now switch to using the Shoe That Grows because of its longer lifetime or because it is donated to them, local shoemakers’ businesses will be harmed. This effect would in fact be in direct contradiction to the improved local economy features that the Shoe’s in-country production seeks to create. To counter this, Because International could leverage local shoemakers as a distribution / retail channel to sell the Shoes, in which case, local shoemakers can at least share in the profits. They could also run training workshops for local shoemakers on how to produce more durable shoes suitable for heavy use in relevant local conditions (durability could be another reason that shoes need to be constantly replaced).

There is also a certain irony in proposing a shoe product as a solution to over-consumption of shoes and apparel. There is a risk that consumers in developed markets will purchase the shoes with good intentions, but in fact continue purchasing other standard shoes for their children as styles change and their children’s feet grow. In this case, the Shoe That Grows no longer replaces shoe consumption, but only adds a new differentiated shoe that makes social value claims to the array of shoes available for consumption. In other words, the Shoe That Grows could actually create more shoe waste rather than reducing it. To ensure they achieve their mission of reducing consumption, Because International needs to invest time and marketing resources in educating their customers on the mission and aims of the Shoe that Grows, in order to effectively change customer consumption behaviour (think Patagonia’s “Don’t buy this jacket” campaign).

Recommendations to improve on the shoe’s SDG contribution

Because of the increased waste issues related to producing and selling any new product, Because International may consider business models that can “close the loop” of its used products. Just as Emma footwear was able to design a circular shoe that was recouped, disassembled, and repurposed, there may be some potential to recycle these used shoes and reuse the materials to fashion new shoes. Such a solution would reduce waste created by the Shoe That Grows and ensure that this innovation is not simply compounding overproduction issues.

Finally, Because International may consider moving into other expandable children’s apparel products. Such products like Petit Pli’s expanding children’s wear line are already offered in developed country markets and seek to address issues of sustainability and durability in children’s clothes (Figure 5). Because International could reposition itself as an apparel source for growing children and increase its sustainability impact by offering many children’s apparel products that can meet children’s needs over five years.

Figure 5 – Petit Pli Expandable Product

References

https://cdn.businessoffashion.com/reports/The_State_of_Fashion_2018_v2.pdf

https://www.ecwid.com/blog/interview-with-the-shoe-that-grows.html

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/finally-shoe-that-grows-with-kid-180955192/

https://www.patagonia.com/blog/2011/11/dont-buy-this-jacket-black-friday-and-the-new-york-times/

Authored by: Alex Walker, Kila Walser, Sonja Riley, Chii Fen Hiu

Thank you for your article that I found very interesting !

I like how you addressed both, benefits and risks.

I still think those kind of shoes have potential in both developing and developed countries. In some developed countries, children wear their summer shoes only a few weeks per year, it can be good to have an option to wear them for several years, especially if they are comfortable.

Thanks for your article, very thoroughly researched, including the risks and possible negative externalities. I agree with the risks you mention, especially whether they are really solving the problem for customers in developing countries. I also wonder whether the five year lifespan is not too long – would a child really want to wear the same shoes for that long? Is it hygienic? What if they lose a shoe (which is not unthinkable in both developing and developed countries), they would need to buy an expensive new pair. It might be worth sacrificing some of the durability to make it easier to recycle, for example.

Surprisingly, this solution employs very simple technology that could be used even for mass market shoe products (not just for low income children). However, with the increased trends in fast fashion and conflicting financial incentives from existing shoe manufacturers, it is highly unlikely that this technology will be employed by the mainstream shoe companies.

Thank you for the post and the presentation. It seems like a relatively straightforward solution that could be well used both in the developed as in the developing world. Perhaps that there is a business model possible that uses an interlinkage between these two to make it an “aspirational” product for both categories. (e.g. “Toms”-model for in the developed world and “famous athletes” inspire usage in the developing world?)

Thank you for a very interesting article! I really like the idea, however, I see 2 possible constraints to address:

1) it is unclear whether the comfort and quality of “growing” shoes if good after several size adjustments: some part are not equally used, and it can be felt by kids.

2) the style of those shoes is now very recognizable – they can be perceived as “shoes for poor”, or can be not adapted by societies where shoe style changes often. I find it very important to position them correctly.